It’s no secret that everyone loves a good mystery, regardless of the time of the year. So if you’re looking for something a bit more daunting after the lovely-dovey stories of Christmas spirit, we invite you to meet a different type of spirit – the one residing in the Hacienda San Isidro.

This debut novel by Mexican-American writer Isabel Cañas has already made its way to Crime Reads’ ‘The best debut crime novels of the year 2022’. It has been proclaimed as ‘deserving of the comparison to Rebecca’ – and we know how that story goes.

In our review, however, we’d like to go beyond the compelling story and address the underlying topic of the book – an entirely different kind of skeletons in the closet.

Whether you’ve already read the book or are planning to read it, you will no doubt notice many untranslated words from Spanish in the English version, like mestizo or criollo.

For someone who’s a beginner Spanish learner and doesn’t know yet that much about the history of Mexico, but wants to familiarize themselves with the culture through literature, the book can be confusing at first. There’s talk about castas, insurgents, and who are peninsulares? Are they talking about the peninsula of Yucatán? Or something else entirely?

While this makes the novel feel more real and believable, we want to bring awareness to the cultural context, for nothing will make you enjoy and appreciate the story even more. This is why we’ve asked our tutor, who’s also a Hispanic literature lecturer, to really delve into the book for you and help you understand the book in all its meaning.

Let’s start from understanding the author.

MEET THE AUTHOR

Isabel Cañas is an author that, when you read her short bio, you’re not sure where to place her – literally. She’s lived in Mexico, Scotland, Egypt and Turkey, among other places. Currently, she’s residing in New York where she’s working on her PhD in medieval Islamic literature and bringing us these gothic gems. Her next novel, Vampires of El Norte, is set to publish in August of 2023.

Reading Mexican-American authors is always interesting because the preoccupation with their heritage is so interwoven with their work. The author’s note at the end of the book tells us a bit more about that. We learn that the author moved nine times during the first eighteen years of her life and that that’s where the story really began.

‘I have a theory about houses,’ a phrase one of the characters likes to say, is actually author’s theory. She noticed not every house she lived in was the same and in one of them she felt like she was constantly watched. This, alongside the desire to write characters that looked like her and her family led to The Hacienda.

According to the author, this is a story about the horrible things people will do for power. Even though this is a horror novel at its heart, it’s also a reminder that houses like Hacienda San Isidro were haunted by their colonial history more than anything else.

So what’s the story?

REBECCA MEETS THORN BIRDS MEETS MEXICAN GOTHIC

The Hacienda, which you can also find under its Spanish name, Donde termina la noche, has often been described as a mix between the classic Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier, and the fairly new Mexican Gothic published in 2020.

We’d like to throw in one more into that mix due to a priest story arc, another classic, The Thorn Birds by Coleen McCullough.

The common elements are all there: the mysterious new husband, a big old house in the countryside, an ex-wife that still haunts the present in every sense. But what makes The Hacienda stand out on its own? To get the feeling for the story, we recommend you watch this short video posted by the author on her Instagram page:

HOUSE AS A CHARACTER

In every good gothic story, it’s the gradual building of suspense what makes it truly gripping. And if there’s something the author does really well, that’s the description of the house, which leaves the impression of it being a sentient being. We’re introduced to the house as if it were a character unto itself. We genuinely worry about its intentions and we dread when we know the main character Beatriz has to sleep there alone.

That being said, the characters themselves are flawed. Beatriz, although brave and stubborn, has quite consciously married for money, not for love. Ironically, she married for the very house that will make her life a living hell. It goes deeper than that, though, as for Beatriz, Rodolfo was a ticket out of her life, where she was treated like a servant due to her mestizo heritage. She brings those traumas and insecurities into her new life and they haunt her at every step just as much as the house.

And where does the handsome witch-priest come into all of that? Even though the author says Andrés’ belief system is fictional, there’s a lot regarding religion of that time that isn’t: the persecutions, the power, the corruption…

The predominant motifs (recurring topic) of The Hacienda are genealogy and discrimination, authority and government, death and resurrection, duty and sin.

We’re now going to dive deeper into the cultural and historical background of The Hacienda with examples from the book.

Just a heads up if you haven’t read the book yet, there might be some SPOILERS AHEAD.

THE CASTE SYSTEM AND THE MEXICAN WAR FOR INDEPENDENCE

Simply put, the Mexican War of Independence was an armed conflict resulting in Mexico’s independence from Spain, that took place between 16 September 1810 and 27 September 1821. In reality, what was happening was a complex political, social and economic matter. Ojo, the War of Independence is not to be confused with Mexican Revolution which started in 1910 against a different leader.

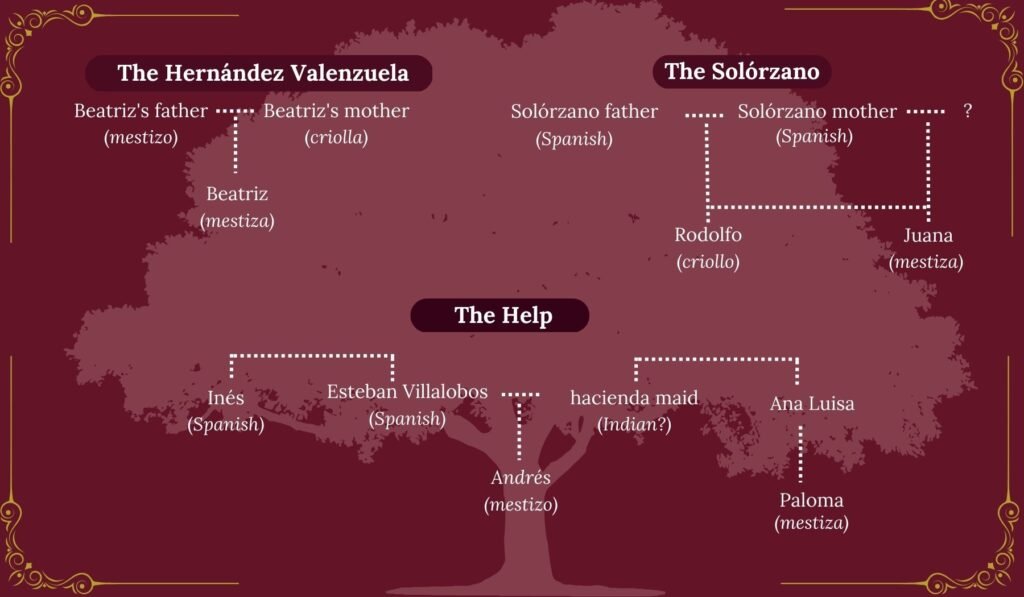

And while the main characters of the story – Beatriz, Andrés, Rodolfo, Rodolfo’s illegitimate sister Juana and all of the servants are fictional, that doesn’t mean they are not real. Their story is the story of millions of others who belonged to their respective casta at the time.

GENEOLOGY AND DISCRIMINATION

Let’s have a look at the family tree of our characters before we explain how the caste system worked in Mexico.

The words that you will see in italics throughout the entire book are undoubtedly mestizo, criollo and peninsular. That’s why we’re going to see what’s their meaning before we get into the nitty-gritty of the problem.

Mestizo: a person from Latin America who is part European, especially Spanish, and part American Indian

Criollo: descendants of Spaniards born in the Latin American colonies

Peninsular: meaning ‘from peninsula.’ In this case, the peninsula is Iberian Peninsula, so peninsulares were Spaniards directly from Spain, opposed to criollo, who for the most part had never been to Spain.

As you can tell from the family tree, we have a bit of a situation going on there, starting from Beatriz’s family. Her mother is a Valenzuela and they’re proud criollos, that is, descendants of Spaniards born on Mexican ground. They’re also firm believers in limpieza de sangre (literally, cleanliness of the blood). The society at the time was rigidly divided in castes, depending on la raza (race). La raza was defined in levels, depending on the percentage of European ancestry. Those with more European blood, more “pure”, had more privilege.

So when Beatriz’s mother married a mestizo, her family disowned her. The woes of Hernández Valenzuela family didn’t end there. Beatriz watched her father being taken away never to return due to his fighting for Mexican independence. After that, Beatriz and her mother were taken in by the only relatives still speaking to them, but were treated abhorrently for a number of reasons: her mother having married a mestizo, her father’s political activities that led to his demise, and her own darker complexion due to mestizo heritage.

Therefore, the caste system was based on one’s race and background. The power structure based on this system ended up looking like this:

So if Beatriz’s criollo family condemned her father’s race and political decisions, how come she ended up marrying a criollo herself? Beatriz’s reasoning is that she didn’t have her mother’s privilege of marrying out of love. All she cared about was getting herself and her mother out of that house where they were treated as dirt.

We find out, however, that Rodolfo worked closely with the insurgents. Seeing how he treats the help, how he looks down on them, Beatriz finds that hard to believe.

Reading about such apparently opposing dynamics can be very confusing for someone who isn’t familiar with the historical side of things.

What were Rodolfo’s true interests, that is, criollos’ interests of that time?

HOW IT ALL STARTED

When the criollo priest Miguel Hidalgo rang the church bells on 16 September 1810, an act that went down in history as Grito de Dolores (Cry of Dolores), this marked the beginning of Mexican War of Independence. At that point, Mexico had been under Spanish control for 300 years.

There are several factors that contributed to the weakening of the Spanish Empire and the ultimate defeat.

A PERFECT STORM

There is many different factors that led to the independence:

- INDIGENOUS REVOLTS: Indigenous population was living in extreme poverty and they were starting to revolt

- CRIOLLOS WANTED MORE AUTONOMY: At the time, criollos held a lot of power in government administration and within the Church. They also wanted more autonomy and control over the finances. At the time, they were inspired by the Enlightenment movement and liberal ideas, especially after the French revolution.

- CRISIS AND WAR IN SPAIN: Spain increased taxes in the 18th century to fund its many wars, which caused administrative problems in its colonies and growing discontent. Furthermore, the need for change was fuelled by the change in Spanish government due to the house of Bourbon replacing the Habsburgs on the throne. The Bourbons were a lot more interested in using the overseas colony as a source of money and started replacing local criollo officials with their own. This ultimately crippled Spanish economy.

- THE US INDEPENDENCE: The spirit of independence was in the air in the 18th century and it spread down south from the neighbouring United States

Ironically, in 1808 Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Spain and dethroned the king Ferdinand VII. This was when criollos started to conspire against Spain, under the pretence that Bonaparte was an illegitimate ruler. They first fought for the legitimate ruler, the imprisoned Ferdinand VII, and then for independent monarchy in New Spain. They used the insurgents, which were mostly formed by farmers, miners and workers at haciendas, for their knowledge of geography to aid them in the war.

The armed conflict lasted 11 years in total and had many different stages. In the end, New Spain became Mexican Empire and Mexican Empire became the Federal Republic.

In Beatriz’s words,

Even though the man who became emperor and papá began the war on different sides – papá with insurgents and Agustín de Iturbide with the Spanish – they worked side by side in the end.’

The Hacienda, Isabel Cañas

Meaning, her father was first on the side of the insurgents. He then formed a coalition with the monarchist conservatives. What was initially a fight against illegitimate Spanish power in the hands of Napoleon’s brother, became a fight for absolute legislative independence from Spain.

However, the Mexican Empire was short-lived. Agustín de Iturbide, the emperor of Mexico, was deposed and his allies executed. A Federal Republic was proclaimed.

Imagine Beatriz’s surprise then when she learned that Rodolfo supported insurgents as well.

To be unpopular with the conservative criollo hacendados, those who clung to their wealth and the monarchy, meant that Rodolfo was sympathetic to the insurgents and independence. It was not unusual for sons of hacendados to turn the tables and support the insurgents, but I did not expect it of the son of old, cruel Solórzano. Perhaps Rodolfo was different from the other criollos.

The Hacienda, Isabel Cañas

This, however, would turn out to be only Beatriz’s wishful thinking. She also had to bite her tongue when Juana, Rodolfo’s bastard sister, spoke with disdain about insurgents and indigenous people.

For a moment, I weighed pointing out that those same people were the forces that all the conservative hacendados and monarchy-supporters had joined in the end of the war, that those insurgents were now the men who ruled the Republic.

The Hacienda, Isabel Cañas

All in all, the period of Mexican War of Independence was a time of great upheaval, and more than anything, of turning tables. Sides were changing whichever way they saw fit. Even though the fight for the common goal did unite Mexican people in the end, there was still a lot of discrimination against each other due to colonial caste system and deeply rooted racism.

And that leads us to our next point.

EL MALINCHISMO IN THE HACIENDA

We can’t talk about Mexico without talking about the civilizations it’s most known for, Mayas and Aztecs. We also can’t mention la conquista, Spanish colonization, without mentioning Hernán Cortés.

The mixing of these two worlds, these two races, led to an entirely new race – la raza mestiza. This is the Mexico as we know it today.

We’ve already learned that Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821, so what did the collective identity look like then? And what does it look like today? Is there resentment towards Spain? Are they refusing any European influence and only embracing their original heritage?

Or is it more complex than that?

You will have noticed the way Beatriz and everyone else of darker complexion is treated. You will also have noticed that mestizos are looked down upon not only by Spaniards, but by Mexicans themselves. What’s more, it’s Beatriz herself who has insecurities because of her mixed heritage. She is afraid of Rodolfo’s refusal because of it. Her mother’s criollo family didn’t even let her stand next to their ‘cream-pale’ daughters at the ball where she met Rodolfo.

There are many such situations throughout the book, especially after Beatriz enters a much more elite circle.

‘Those were eyes that did not see faces that were not peninsular or criollo. There were many such pairs of eyes among the hacendados and their families.’

‘You’re nearly as lovely as Doña María Catalina, though quite darker.’

The Hacienda, Isabel Cañas

Malinchismo, as described by many Mexican academics, is a phenomenon of hating and blaming everything that is foreign, particularly Spanish, while at the same time wishing for it and subconsciously despising their own ethnicity.

We could argue that the race, la raza, and not the story of a haunted house, is the main topic of this book. For every aspect of the story, both fictional and historical, is determined by one’s belonging to casta.

To understand where malinchismo is truly coming from and how it has plagued the Mexican society for centuries, we have to look further back.

MALINCHE: MEXICAN POCAHONTAS

The term malinchismo stems from the name of one woman – Malinche, Malintzin or Doña Marina.

But what has Malinche done to deserve such a bad denomination?

In 1519, la Malinche was one of the 19 women offered as a tribute to the Spanish by the Indians of Tabasco. She ended up marrying Hernán Cortés and playing a crucial role in the conquest of Mexico.

She was baptised as Doña Marina and forced to learn Spanish. As someone who knew Yucatec and Nahuatl (Mayan and Aztec languages), the culture, the social and military customs of Indian people, she was an invaluable asset for the Spanish. She served as an interpreter and advisor to Hernán Cortés. He kept her so close that she was always depicted standing next to him in Aztec codices.

The son they had together is considered as one of the first mestizos that came out of the conquest of Mexico. This is why la Malinche has been attributed mythical connotations over time. She became known as La Madre del Mestizaje (The Mother of the Mixed Race).

The figure of la Malinche is as controversial and as contradictory as the term malinchismo.

For many, she’s the symbol of treason. For others, she’s the victim of cultural clash, much like Pocahontas, who was offered by her father to the English and ended up siding with them.

Nowadays, malinchismo is used for all those who value the other, the foreign, over their own. You might think that this inferiority complex has vanished with the end of colonialism and the caste system. However, according to Octavio Paz, this is something that is very much part of Mexican identity. It’s part of their collective unconscious.

BEHIND MEXICAN MÁSCARAS

In case you didn’t know, Octavio Paz is a Mexican writer who won the Nobel Prize in 1990.

He wrote an incredibly insightful and honest book of essays, The Labyrinth of Solitude: Life and Thought in Mexico. In his essays, he dissects Mexican character, going behind ‘máscaras mexicanas’ (Mexican masks) with brutal honesty towards his compatriots. He’s also dedicated an entire chapter to la Malinche, titled The Sons of La Malinche.

When we shout ‘Viva México, hijos de la chingada!’ we express our desire to live closed off from the outside world and, above all, from the past. In this shout we condemn our origins and deny our hybridism. The strange permanence of Cortés and La Malinche in the Mexican’s imagination and sensibilities reveals that they are something more than historical figures; they are symbols of a secret conflict that we have still not resolved.

Octavio Paz

He claims that Mexicans need to accept their duology in order to be whole. As it stands, they want to be neither Indian nor Spanish. This falls in line with what we see in the book: criollos are descendants of Spaniards, but they don’t want to be Spanish, they want autonomy. At the same time, they believe themselves to be superior due to their white skin – a trait that’s inherently European, the other.

The Hacienda, although fictional, gives us a good representation of this due to the very clear and, by default, discriminatory caste system that existed. And we could argue, still exists deep down in the collective unconscious of the Mexican nation.

So can we still spot examples of malinchismo in modern Mexico?

If you turn on Mexican forecast or pay attention to the skin tone of most actors and beauty queens on TV, you’ll notice they’re mostly white or of lighter complexion, which isn’t representative of the majority of people living there, who have indigenous features. At the same time, there’s a strong anti-Spanish feeling and propaganda going on due to La Conquista.

This leads us to the conclusion that Octavio Paz was right about the existing dichotomy within Mexicans. There’s an obvious shame of indigenous ancestry (indio is often meant as an insult even by people of clearly mixed heritage), and resentment towards Spanish part of heritage on the other hand. However, it’s clear which one is considered more “desirable”. If you go back to the definition of malinchismo as we described it, that’s exactly what it is.

After these heavy topics, let’s see if you’ve noticed other, lighter and less tragic aspects of Mexican culture in the Hacienda.

MEXICAN CULTURE AND MYTHOLOGY IN THE HACIENDA

Being a gothic novel at its core, there are many scenes throughout The Hacienda that will keep you on the edge of the seat. There’s one in particular that stood out to us, and not just because of the visual representation. Without giving away too many spoilers, there’s a scene where Beatriz wakes up and confronts what she thought was la Llorona.

‘At first glance, I thought it was the apparition we called the Weeper. A woman in white with black hair falling into her face. She stumbled up the aisle, sobbing uncontrollably. Water trailed behind her, leading from the door.

But I knew the Weeper well. It was not her season, not her time. Nor her place to appear.

This was not a spirit.’

The Hacienda, Isabel Cañas

La Llorona, also known as the Weeping Woman or The Woman in White is one of the most represented figures from Mexican mythology. There are many versions of this story, but they all agree on that la Llorona is a woman dressed in white, who has killed her children and is now wailing incessantly for the crime she committed. She’s known for her bone-chilling scream, ‘¡Ay mis hijos!’

Interestingly enough, there’s a theory that says la Llorona is based on la Malinche. Allegedly, the reason why la Llorona appears is the regret for abandoning her people. The infamous scream in this context is the lament of Latin American nations for the hardships and the horrors endured during la Conquista.

We don’t know whether this was intentional or not, but it seems more like a nice touch, especially because of Beatriz’s reaction. ‘But I knew the Weeper well.’ As any Mexican undoubtedly would.

VEGETATION

Apart from the caste system terms, other words in italics are mostly related to the vegetation Beatriz encounters on the hacienda. We know that Rodolfo is in alcohol production business, but most of us have never even heard of pulque or any of the related terms that are specific to Mexico. Let’s look at an overview of the most important terms:

Maguey – an agave plant, of a type used to make alcoholic drinks.

Pulque – an alcoholic beverage made from the fermented sap of the maguey plant. It’s traditional to central Mexico, where it has been produced for millennia. It has the color of milk, somewhat viscous consistency and a sour yeast-like taste.

Tlachiquero – collector of maguey sap for production of pulque.

We also see Juana mocking Beatriz for wanting to have a garden instead of just maguey, which she doesn’t find beautiful.

‘Maguey is resilient,’ she said flatly. ‘It’s an admirable trait.’

Rodolfo’s eyes slid across the table to her, their blue no longer brilliant, but icy. ‘Beauty is also an admirable trait,’ he said. A playful retort and delivered utterly without warmth. ‘This the maguey lack, I believe.’

‘Then you’re not looking hard enough.

The Hacienda, Isabel Cañas

There’s almost a patriotic sentiment to Juana’s fierce defence of maguey. It comes as no surprise that maguey is on the cover of the book, not just because of the context, but because it has become as synonymous with Mexico and Mexican landscape as its people.

DAY OF THE DEAD

At the very end of the book, there’s mention of preparations for the 1st of November, el Día de Muertos.

It was the talk of the village, passed from hand to hand with loaves of pan de muerto as families prepared for the first of November, as they gathered in the graveyard behind the capilla and exchanged news over the crackling of small bonfires.

I had spent the holiday evening indoors with Paloma. We scattered bright cempasúchil petals around a small ofrenda for her mother…

The Hacienda, Isabel Cañas

We thought it was very fitting and within Mexican spirit that the Day of the Dead was left for a happy resolution at the end, as it’s not considered a sad occasion in Mexico and is not celebrated as such.

If you’d like to know about pan de muerto, cempasúchil, ofrenda , the difference between Halloween and Day of the Dead, and much more, you can check out our own whodunnit original learning story resource dedicated to the topic. Pst! Pst! La Llorona might make an appearance alongside another emblematic Mexican character!

JOIN RLC CLUB DE LECTURA

We hope you liked the review of our book of the month. We’re proud to announce that we have now started a book club!

We meet every month to discuss a popular book of choice. You can read the book in any language you like, but the discussion will always be in Spanish, which makes this for a great practice if your speaking skills are rusty or in need of developing.

Our professional tutor will have materials ready for each class to make this an engaging and valuable experience. You will not only be reading for the sake of a good story, but you will also be learning about culture and history of Latin America and Spain through literature. We’ve already learned a lot about Mexican history through this chilling gothic debut, so we’re going to keep building on that knowledge.

The next book on our list is set during Mexican Revolution – a classic of Mexican literature Como agua para chocolate by Laura Esquivel. Join us and read it with us in the month of February, 2023!