‘Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.’

This incredible first sentence is one of the most famous first-liners in the history of literature, up there with Anna Karenina. It’s only fitting, as it was this sentence that popped into Gabo’s, as Gabriel García Márquez is lovingly called, head while driving, making him turn the car around and completely overtaking his life in the next 18 months.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is, undoubtedly, one of the most discussed, analysed and beloved works of Hispanic American literature. It has recently come into a different, and completely unexpected limelight due to the upcoming Netflix adaptation.

As any fan of Gabo’s will know, just the fact that there will be an adaptation of this classic is controversial in itself. Why? Because Gabriel García Márquez has explicitly stated that he wrote his book ‘against the cinema.’

It comes as no surprise then that many are nervous about Netflix’s take on One Hundred Years of Solitude. Not only is it notoriously difficult to translate to the screen due to magical realism enveloping the story, its rich tapestry of symbolism, the lack of dialogue and linear timeline, but it is also being adapted by a North American giant company, which is precisely one of the book’s underlying topics.

To fully understand all the reasons that make this such a challenging book to adapt, we need to go to the source. What inspired García Márquez to write such a unique story, what was its impact, and what is even magical realism? And for those of you who are anxiously awaiting Netflix’s adaptation, what can you expect from it?

HOW THE IDEA FOR ONE YEARS OF SOLITUDE BECAME REALITY

Even though the anecdote of how García Márquez cut short the family trip to Acapulco to write his novel is true, there’s much more to it. And the story of how One Hundred Years of Solitude came into existence is almost as interesting as the novel itself.

He might have written it in Mexico, but the pages live and breathe his natal Colombia – where it all began. Just like many struggling families, his parents had to leave him in care of his grandparents while they sought out a better life for them all elsewhere. The events and the characters from One Hundred Years of Solitude are heavily influenced by his grandparents and his hometown, Aracataca. His grandpa was a colonel (sound familiar?) who was also very adept at storytelling. He showed Gabo how to craft goldfish figurines, introduced him to the circus, and yes – the ice.

His grandmother was the inspiration for the matriarch of Macondo, Úrsula Iguarán. She was a superstitious woman, as adept at interpreting dreams and talking to the dead as her husband was at telling stories. In their household, however, that wasn’t regarded as something extraordinary – it was as normal and everyday as drinking a glass of water. This is the primary characteristic of a literary movement called magical realism that we’ll get to later.

Those first, crucial experiences were interrupted when Gabo’s parents were finally able to bring him to Baranquilla with them. It would be long 11 long years before García Márquez returned to Atacarata, during which it completely transformed. Young writer in the making was flabbergasted at seeing his childhood town dusty, neglected and practically abandoned – it was a ghost town rather than the childhood home from his memory. This was when he sat down to write, intent on telling the history of the place, just like his grandfather had taught him. However, the words just weren’t coming. It was when the seed for writing the story about the Buendías was planted – it just wasn’t the time for it to come out yet.

THE CHALLENGING 18 MONTHS

Years went by and a lot had changed in Márquez’s life.

He first worked as a reporter at Prensa Latina in New York, but after receiving death threats due to his political connections with Fidel Castro, he sought exile in Mexico with his family.

They were on their way to Acapulco for a holiday when that famous sentence came to his mind. It meant just one thing: it was finally time for the story to come out. In his own words, ‘Era escribir o morir’ (It was either writing or dying).

He quit his job as a screenwriter and put his wife Mercedes in charge of the family finances so that he could focus on writing. This was both a good and a bad time for him and his wife. They didn’t have money but he was writing maniacally.

Mercedes had to pawn her jewellery, sell some household appliances, and their friends pitched in with food. In return, they only asked for Márquez to read them passages from the novel. Little did they know, they were listening to the beginnings of a novel that only Don Quijote would top in the future.

In the end, even the little money they had ran out. They were due 3 months’ worth of rent when the landlord rang them demanding payment. In the end, he kindly agreed to let them pay everything in 7 months, which meant Márquez now definitely had to finish the book in 6 months, without even knowing if the book was going to be successful

PUBLISHING ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Another famous anecdote from this time is the couple’s trip to the post office once the book was finished. After weighing the 700 pages of manuscript, it turned out they only had money to send half of the book to Sudamericana Press in Argentina, so that’s what they did.

The only problem was – they sent the last part by accident. They sold a couple of more items from the house to collect enough money to send the second half. After finally sending the whole book, they got out of the post office and his wife said: ‘Now we just need for this book to be bad!’

One Hundred Years of Solitude sold 8.000 copies just in its first week of release in 1967. It became part of the publishing phenomenon known as Latin American boom, as well as one of the most representative novels of magical realism, earning García Márquez a Nobel prize in 1982.

But what is even magical realism and what does it really mean in the context of the novel, but also of Latin America?

THE SOLITUDE OF LATIN AMERICA

We’ve already seen how Márquez’s grandmother regarded what most would consider fantasy, that is, something that’s impossible. This is one of the reasons why magic realism resonated so much with the people of Latin America. Much like the rural parts of Galicia in Spain where the everyday life coexists with the mythology, the same can be said for many parts of Latin America. Just think of all the beliefs revolving around the Mexican Day of the Dead.

And if we look at the chronicles written by Spanish conquistadores, who were completely taken aback by the colourful flora and fauna of Latin America, we’ll realize that it has always bordered on the fantastical and mythical in the eyes of the rest of the world.

And vice versa: Spaniards arriving with their galleons and horses were a thing of fantasy for the local inhabitants. They hadn’t seen a horse before any more than Spaniards had seen a macaw.

What is more, what made la Conquista so easy for Spain in some parts of Latin America was the lack of resistance from the gods-fearing indígenas. To them, Spaniards might as well had ridden in on a thunder, fulfilling all of their cataclysmic prophesies.

Márquez wanted to capture the post-colonial reality of Latin America. An entire continent forced to relive tragedies of the past in the same way the characters are repeating the mistakes of their predecessors. Because when people think of the modern Latin America, they often don’t think of peace. They think of the kidnappings Colombia is known for, of drug cartels running cities all over Latin America, of deeply rooted corruption in police and government, civil wars, dictatorships and, consequently, the constant revolutions. Latin America has known no peace since its independence from Spain, contrary to what one might assume.

NEW RACE – NEW WORLD OF ABSURDITIES

We could argue that this is the consequence of the inevitable duality within all latinos, children of a new race. We’ve written more in depth about this topic in our take on the gothic novel The Hacienda and the Mexican War of Independence.

On one side, there’s the mentality dating back to the colonialism and the caste system. On the other, there’s the chaos that unfolded after the wars of independence, acquiring almost absurd proportions that are so well reflected by the concept of magic realism.

The theme of thirst for knowledge, the progress and what that ultimately does to the otherwise unspoiled Macondo, as civilizations of Latin America once were, underlines the novel. This is just one of the many extremely illustrative symbols that can be found in the novel.

As Márquez himself had stated in his Nobel prize speech: ‘…we have had to ask but little of imagination, for our crucial problem has been a lack of conventional means to render our lives believable. This, my friends, is the crux of our solitude.’

The absurd has become the new normal, and the absurdity of magic realism − the absurdity of Latin America.

WHAT IS MAGIC REALISM?

Even though Latin American writers made magical realism into what it is today, we can find tentative roots of it elsewhere. The term magischer realismus was first used in 1925 by German art critic to describe New Objectivity, a style in painting that was popular in Germany at the time. The definition of this magic realism, however, has more to do with how magical everyday objects can look when you really stop and look at them, than with actual magical occurrences.

Still, the idea found fertile ground in Latin America and got extremely popularized by the writer Alejo Carpentier who was exposed to this style during his trip to Paris. He further developed this concept into what he called realismo maravilloso, or marvelous realism.

The term magic realism was coined in 1955 by literary critic Ángel Flores, who anointed the genius Argentinian author Jorge Luis Borges the predecessor of this movement.

FANTASY VS MAGIC REALISM

We know, as the word itself suggests, that magical realism incorporates some magical elements into the story. But how can we tell that a book falls under this category, as there are many books with fantastical elements?

When reading a fantasy novel, like Lord of the Rings or Harry Potter, there’s always going to be world-building that accommodates and explains the existing magic system. Then there are horror stories that are set in real world, but with phantasmagorical elements that the characters are trying to figure out. Therefore, the key thing that categorizes a story as magical realism, is that the magical element is not questioned in any way, but accepted as completely normal.

In a story belonging to magical realism, we’ll usually find:

- Realistic setting. Macondo doesn’t exist in real world as such, but it might as well be any decrepit town/village in Colombia, so the setting is in this world.

- Magical elements are regarded as normal. In order to normalize and enhance this effect, we don’t get any explanation for the how and the why of things. For example, the dead in One Hundred Years of Solitude are not scary ghosts from stories. What is more, the ghost of Prudencio Aguilar serves as a comic relief, who torments his relatives but no one questions his existence as a ghost.

- Critique. This is often the critique of the existing hierarchy in the society of American imperialism. Márquez represented a true historical event that his grandpa told him about, known as The Banana Massacre in 1928, which was a massacre that followed a strike at the United Fruit Company plantation. Colombia, their own country, didn’t side with the workers, choosing their commercial interest in the foreign market. Márquez exaggerated the numbers of the dead in the style of magical realism. This disproportion so characteristic to the genre serves the purpose of highlighting the problems of Latin American societies.

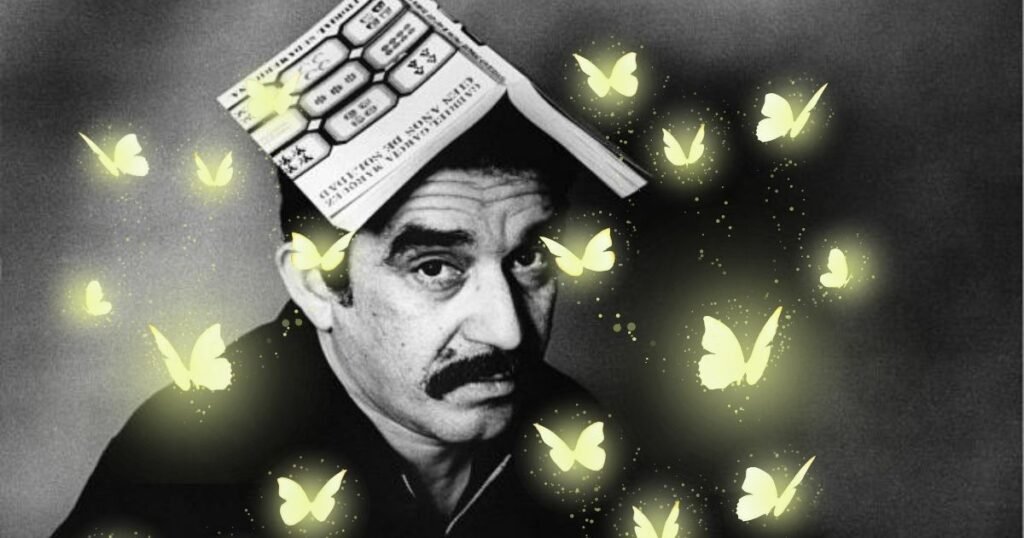

- Fantasy as an extended metaphor. Represents something internal to the protagonist. One of the most famous symbols of One Hundred Years of Solitude are, without a doubt, the yellow butterflies. They’re constantly fluttering around Mauricio Babilonia, representing his love for Meme. But then he was shot in the back just before one of their rendez-vous and spent the rest of his life in bed, alone and separated from Meme. The butterflies, however, never left him and kept tormenting him until his death. Thus, the yellow butterflies become a metaphor for loneliness and impossible love.

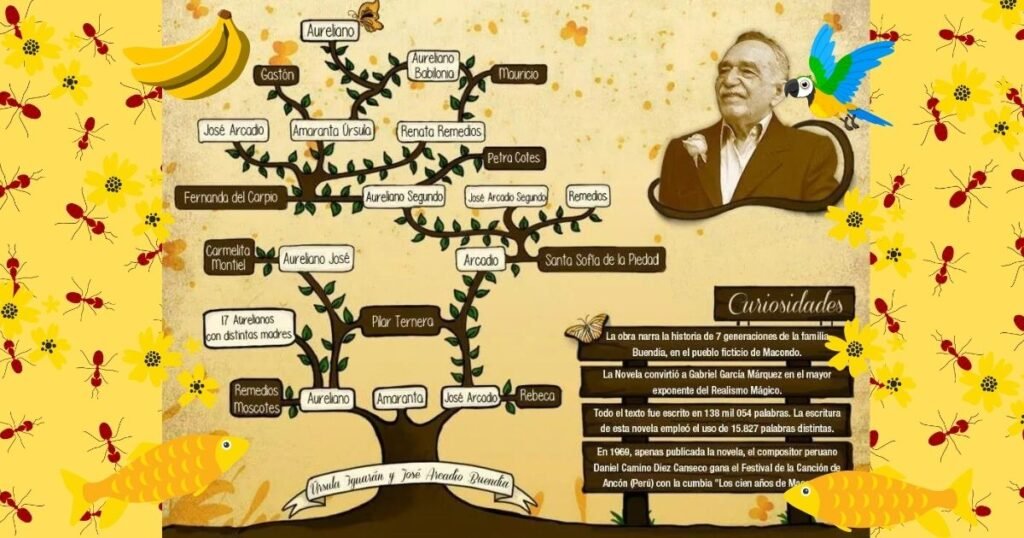

- Unique plot structure – time is not linear. This is especially prominent in One Hundred Years of Solitude which tells the story of 7 (!) generations of the Buendía family.

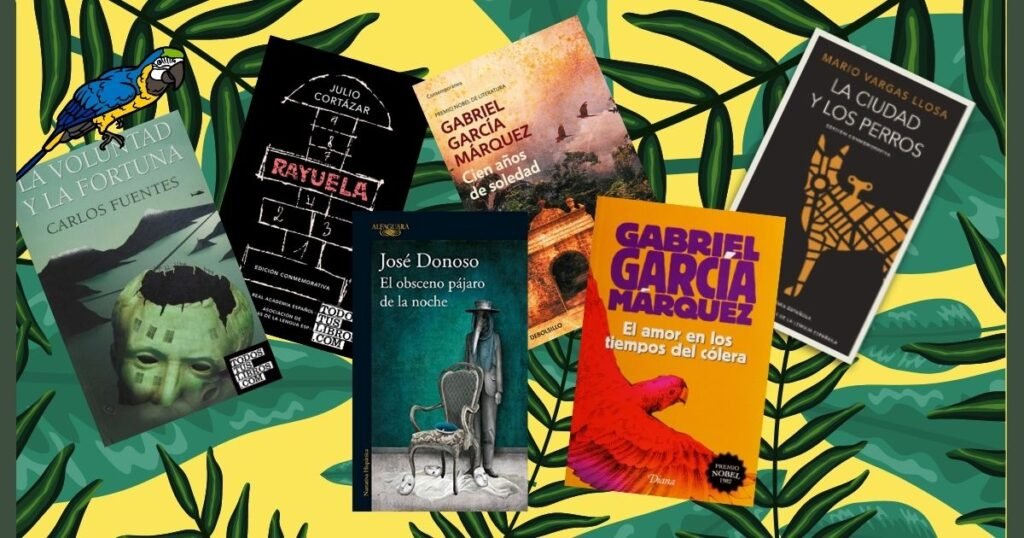

THE LATIN AMERICAN BOOM

How many Latin American novels can you think of from the beginning of the 20th century? Probably not many, if any.

That’s not to say they didn’t exist, but they had no real commercial success or exposure. They were mostly copying European tendencies such as Modernism and Romanticism.

All of this changed, however, in the 60s and 70s of the past century, when the world got to see Latin American literature in a completely new light. Latin American writers didn’t have to look for the exotic in the style of European Romanticism anymore: they were the exotic.

As the name indicates, boom was the explosion of Latin American authors on a global scale. It is predominantly associated with the authors Julio Cortázar (Argentina), Carlos Fuentes (Mexico), Mario Vargas Llosa (Perú) and García Márquez (Colombia). There was no manifest and no formal grouping that we usually associate with new literary movements. The writers were mostly individuals living in exile who were well versed in world’s literature.

The boom is often characterized by the critics as the publishing phenomenon, first and foremost, rather than literary flourishment. The translations, the publicity and the wider circulation opened new doors to the authors from that part of the world. One Hundred Years of Solitude, in particular, was a milestone in the history of publishing in the Spanish language for its level of sales. It also normalized the new aesthetic established by the boom, although not all of the authors belonged to magical realism genre.

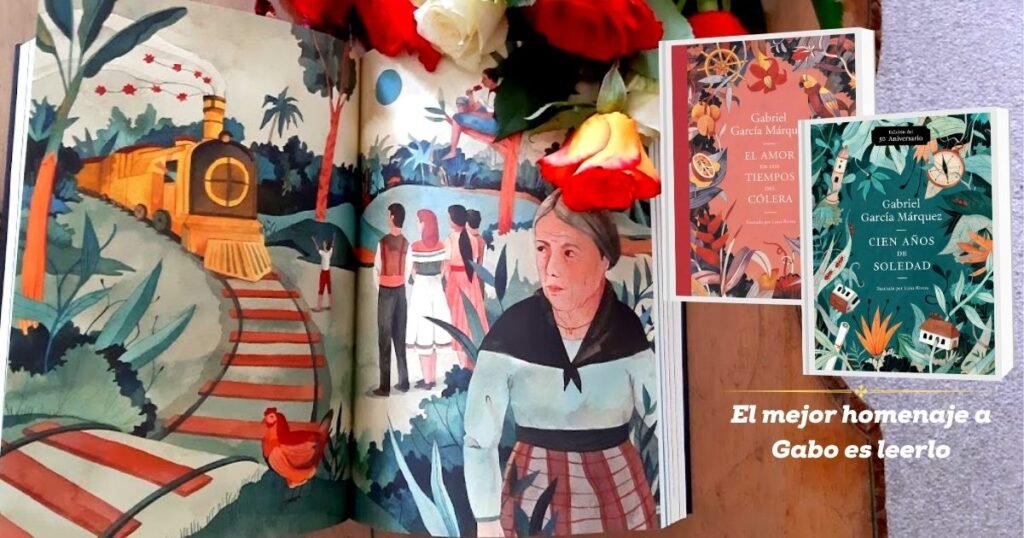

As for One Hundred Years of Solitude, not only did it not fall silent after the boom, it has become increasingly popular over the decades. In 2017 special editions for One Hundred Years of Solitude and Love in Times of Cholera were made to honour the 50 years since the publication. Colombians consider the novel to be national cultural heritage, so you can understand the nervousness surrounding the Netflix adaptation.

So let’s see what the story is about and what makes is so hard to adapt for screen.

THE STORY OF ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

By now, we know that One Hundred Years of Solitude is about the ups and downs of 7 generations of the Buendía family, just like we know that their story is a metaphor for the entire Latin America.

But how does Márquez manage such an enormous task in a way that’s still compelling to the modern-day readers? We won’t go into the nitty-gritty details of the story because that might take, no pun, a hundred years. Instead, we recommend you watch this beautiful animated breakdown of One Hundred years of Solitude by TED-Ed to get the feeling for the story.

Some readers believe that this sort of whimsical animation would be perfect to convey the story and the atmosphere of the book. It’s vague and magical in just the right amount, while the TV show format ought to be more confined by the reality.

We’ve already mentioned some of the other factors that make One Hundred Years of Solitude a difficult book to adapt. It abounds in symbols and there isn’t a lot of dialogue to help the dynamics on the screen.

And now let’s dive in deeper into the elements that make this such a unique piece of work.

SYMBOLISM: MÁRQUEZ’S ICONIC YELLOW

Countless research papers and thesis have been written on the symbolism of the One Hundred Years of Solitude. For clarification purposes, symbol in literature is an abstract idea conveyed through an object, animal, color, sound or even a person.

We’ve seen one such example in the yellow butterflies representing impossible love. And while the use of symbols is common practice in writing, they are even more prominent and memorable in One Hundred Years of Solitude due to magical realism.

So much, in fact, that some of the symbols went beyond the literature students’ classroom and acquired almost legendary connotations. It suffices to say that hundreds of yellow paper butterflies were released during the ceremony for Gabriel García Márquez’s ashes in Colombia in 2014. There was even a yellow butterflies monument built to honour his work.

You might notice that there’s a lot of yellow in the book: the butterflies, the goldfish, the yellow flowers, and even the yellow train that symbolizes the arrival of American imperialism into Macondo. We usually associate the colour yellow with sunshine, something that’s bright and positive, but these aren’t symbols of happiness. So what does this colour represent for Gabo?

The period during which Spain was at the height of colonial, economic, political and artistic power is commonly referred to as the Golden Age (1580 −1680). Therefore, yellow symbolizes death and decay associated with la Conquista and gold, by extension, represents imperialism. Yellow is also one of the colors on the Colombian national flag.

Sometimes, the symbols can be so iconic that we come to associate the author with them. What the raven means for Edgar Allan Poe, the madeleines for Marcel Proust and the giant bug for Kafka, those are the yellow butterflies for García Márquez.

Symbols in One Hundred Years of Solitude: mirrors (Macondo as a reflection), ice (invention and progress) yellow butterflies (impossible love), yellow flowers (death), yellow train (American imperialism).

MOTIFS IN ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Motif is a literary technique that entails a certain element being repeated throughout and that has symbolic significance to the novel. That being said, motif is not the same as symbol. The main differentiating point is that motif must recur in a work (appear many times), while a symbol could appear just once or twice.

For example, one of the main motifs in One Hundred Years of Solitude is − solitude, which conveys the larger theme of Latin America’s isolation in the wake of social and political turmoil.

Another important motif is the human nature. The story of how Macondo came to be and how it ultimately fell is, in a way, the story of mankind retold. Characters find themselves unable to avoid the repetition of history in Macondo, that is, Latin America.

They are often visited by ghosts, who represent the past, and the new generations of the Buendía family are often reincarnations of the previous one.

Let’s just stop for a moment to ponder about the fact in the Buendíá family there was 17 Aurelianos in total. We find this especially amusing when we think of how close this is to the reality of Latin American families. How many times have you heard that the son is named same as the father and the father same as his father?

This is one of the reasons why we recommend to read the book with a family tree prepared, or even better, to make your own as you go. Some editions even come with a family tree included.

“…because races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth.“

— Gabriel García Márqueze

By repeating the mistakes of their ancestors, members of the Buendía family are falling into the vicious cycle from which they cannot escape.

How that ends, exactly, we leave for you to find out − on the last pages of One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Motifs: genealogy and fate, death and reincarnation, solitude and oblivion, love and lust, human nature and progress

STYLE – GABO’S UNIQUE WRITING VOICE

Picturesque symbols and countless Aurelianos are not the only thing One Hundred Years of Solitude is known for. Its prose (written language in its ordinary form, that is, not poetry) is dense and complex. Every sentence had been thought over and polished during those maniacal 18 months of creation.

When we say that Márquez’s prose has a rhythm, we mean that quite literally. He was a big lover of music and it influenced his writing greatly. He was listening to the Hungarian composer Bela Bartok, whom he greatly admired, while writing One Hundred Years of Solitude.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is most certainly not an easy read. It requires focused attention and a printed-out family tree. It is one of those books that hide more than they reveal. Many claim to have read it multiple times, only to find more details, more layers, with each reread. They enjoy coming back to it to discover new clues, or simply – to enjoy the richly composed sentences.

WHAT CAN WE EXPECT FROM NETFLIX’S ADAPTATION?

In 2019, when Netflix announced that it acquired rights to adapt One Hundred Years of Solitude into a series format, reactions varied, mostly due to the well-known opinion of García Márquez on this.

GABRIEL GARCÍA MÁRQUEZ AND THE CINEMA

Gabriel García Márquez passed away in 2014 after a long battle with cancer. During his entire life he repeatedly refused to let his magnum opus be made into a movie. He believed it just wasn’t possible due to the constraints of the medium.

Another reason why Márquez preferred for the story to remain inside the pages, as he stated in an interview with Caracol Radio in 1991, was because he wanted for the readers to be able to imagine the characters for themselves and not for TV to define them for them.

Furthermore, in one interview he described his relationship with the cinema as ‘an uneasy marriage.’

We learned from his biography that Márquez worked as a screenwriter, so we know that he did, in fact, write movies himself. However, there wasn’t much love lost there. According to Márquez, movies have technical limitations novels don’t have. During one of his disputes with the movie industry, he proclaimed that he wrote One Hundred Years of Solitude against the cinema.

He simply believed that books should be books, and movies should be movies.

So what changed?

NETFLIX’S PROMISE

It was García Marquez’s sons, in the end, who conceded the rights to Netflix and this was their reasoning:

For decades our father was reluctant to sell the film rights to One Hundred Years of Solitude because he believed that it could not be made under the time constraints of a feature film, or that producing it in a language other than Spanish would not do it justice,” García said. “But in the current golden age of series, with the level of talented writing and directing, the cinematic quality of content, and the acceptance by worldwide audiences of programs in foreign languages, the time could not be better.

A TV show rather than a movie will most definitely allow the rich tapestry of One Hundred Years of Solitude to unfold more freely.

What else did Márquez’s sons demand from the streaming giant?

The adaptation will be in Spanish in its entirety. Another requirement was for the series to be recorded in Colombia for the most part and to use Latin American actors. The cast hasn’t been revealed yet, but one thing’s for sure: we’re not expecting Antonio Banderas to play José Arcadio Buendía.

Netflix’s One Hundred Years of Solitude TV series is going to be directed by the Argentine’s director Álex García López (The Witcher) and Colombian director Laura Mora, with Márquez’s sons as executive producers. His son García Barcha revealed in 2019 that the series will consist of 2 seasons and 20 hours in total to allow the story to be adequately told.

SNEAK PEEK INTO ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF SOLITUDE

Netflix released its first trailer for the series on the 21st of October 2022 so we know that the production has started although we don’t have the official release date yet.

Most were truly surprised to find out about the adaptation, knowing Márquez’s feelings on it and how difficult magical realism is for movies. Nevertheless, reactions are overall positive and expectations high. Just like with any beloved book, fans want just one thing: don’t ruin it.

Some latinos have commented that they will be happy to see a TV show about Latin American culture that isn’t about drug cartels and Pablo Escobar – another reason why the adaptation of One Hundred Years of Solitude is so anxiously anticipated.

We don’t know what Márquez would think of the Netflix adaptation, whether he’d share his sons’ point of view or he’d see Netflix as the yellow train rolling into his Macondo. One thing’s for certain: One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez is the story of Colombia the world should know about.

One Hundred Years of Solitude took the world by storm immediately after its publication in 1967 and it is still one of the most widely discussed works of literature. We took a peek behind the curtain and saw that the conditions under which Gabriel García Márquez wrote his masterpiece were far from ideal. He and his family struggled financially during the 18 months that took Gabo to finish the manuscript and relied on the kindness of their landlord and friends to get by.

The book that he wrote in such a frenzy landed him a Nobel Prize in 1982. In his speech, he addressed the struggles Latin America faced as a society, reflected in the mirrors of the ficticious town Macondo. He found their situation so absurd, so disproportionate to the parameters of reality, that he felt magical realism was the only way to successfully convey their story.

The book was part of the so-called boom phenomenon, an incredible commercial and publishing success of Latin American authors in the second half of the 20th century.

The story of One Hundred Years of Solitude revolves around the 7 generations of the Buendía family. Led by their basic instincts, they are the perpetrators of a vicious cycle, always repeating the mistakes of their ancestors over and over again. The novel is known for its vivid symbols, like the yellow butterflies that represent impossible love.

Márquez associates the yellow colour with Spanish Golden Age, so in his book, it’s the symbol of death and decay. His magnus opus is also read and reread for the rich, complex prose and well-crafted sentences.

Due to magical realism in the book, heavy symbolism and dense text with little dialogue, Márquez never believed One Hundred Years of Solitude to be apt for screen adaptation. So when Netflix announced that it had acquired the rights from Márquez’s sons in 2019, the public was taken aback, although hopeful and excited to see the beloved story come alive on the screen − as long as it’s respectful of the book.

We can tell just by the reactions to the Netflix’s trailer that One Hundred Years of Solitude has become Colombian cultural heritage and that many would love to see its story broadcasted to the rest of the world, rather than the usual genre we associate with Latin America. One Hundred Years of Solitude is not only an eternal classic of magical realism, it’s also the proof that sometimes the best things in life come out of hardships – and that the real magic happens when we don’t give up.

PREPARE FOR THE ADAPTATION – LEARN SPANISH WITH RLC

Want to take a language course with your significant other? Perhaps you want to travel with your friends? Or engage in a family learning activity on Saturdays? Our small group learning with a discounted price for families and friends is the perfect learning option for you!

With over 13 years combined of qualifications and experience teaching Spanish at universities and language schools across Europe, we are immensely dedicated to our craft, Spanish language, culture and education. We teach Spanish through a carefully planned out and well-tested method that has brought desired results to all our students.

Book a FREE Educational Assessment and meet us with no need to book any lessons at the end!