There’s no doubt that Latin America is often associated with passion, dance, love…This might seem a bit stereotypical but you know how they say: where there’s smoke there’s fire. It’s also known for its delicious cuisine. All of that and more, you can find in Like Water for Chocolate.

This is why we’ve chosen this Mexican classic for our book of the month – and what better time than February. That being said, Like Water for Chocolate is a lot more than a mere love story. In this relatively short novel (around 200 pages), there’s a lot of cultural and historical context as well.

In order for you to fully experience it, we’ll be delving deeper into all of its aspects. This includes the Mexican Revolution, the magical realism genre and the literary devices used by Laura Esquivel.

And if that convinces you to read the book, you can join our discussion at the end of the month! Just be warned – there are some spoilers ahead.

RISE TO POPULARITY

The theme of forbidden love is nothing new in literature. But have you ever read a love story made in Mexican kitchen with a pizca of revolution and magic? Indeed, what made Like Water for Chocolate such a popular read since its publication in 1990 are its unique ingredients.

It comes as no surprise then that it became a global phenomenon overnight. It was the top-selling novel in Mexico for two years, got translated in 36 languages and sold 7.000.000 copies worldwide. Moreover, the movie of the same name became the highest-grossing foreign language movie ever released in the United States.

So what’s all the fuss about?

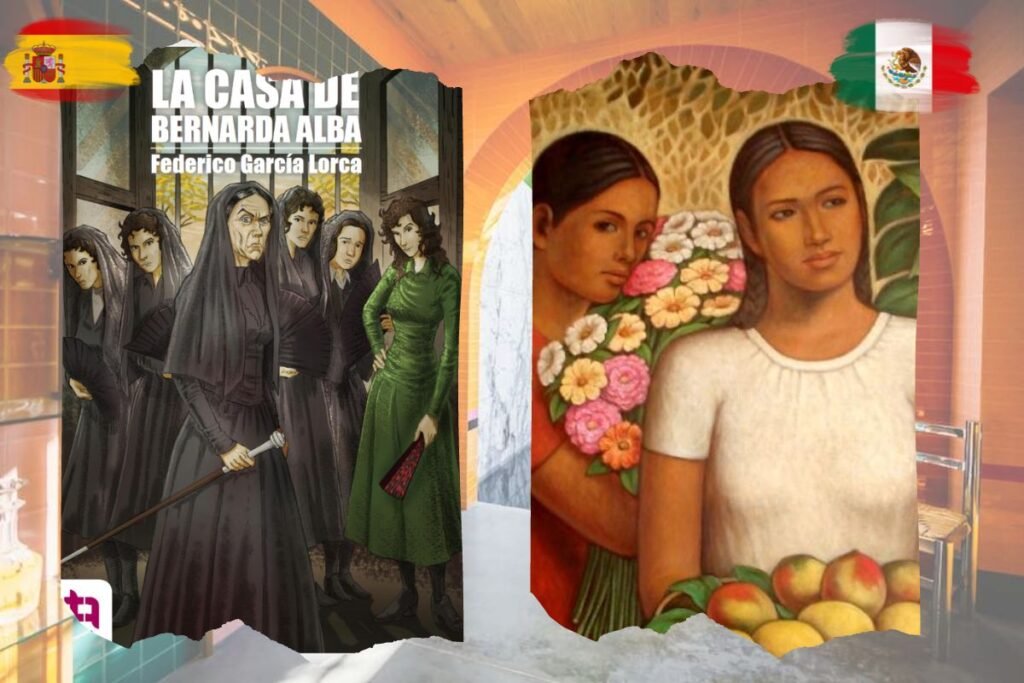

MEXICAN LA CASA DE BERNARDA ALBA

The story revolves around Tita, a 15 year-old Mexican girl living in an incredibly strict household. Not only that, but she’s fallen victim to the tradition that makes no sense. She, as the youngest daughter, is to never marry because she’s supposed to look after her mother until she dies. As the destiny will have it, she’s fallen crazy and irrevocably in love with Pedro, their neighbour. Her tyrannical mother, however, offers him her sister Rosaura instead and he marries her so he can be close to Tita. As you can imagine, things will get complicated.

This dichotomy between passion and oppression as well as the rich imagery inevitably reminds us of another classic of Hispanic Literature. The House of Bernarda Alba is a play written by Federico García Lorca in 1936. There we also have the figure of tyrannical matriarch in the form of Doña Bernarda. She imposes an eight-year mourning period on her daughters in accordance with family tradition. During that time, they mustn’t leave the house. Similarly, Tita’s world ends at the kitchen door. There’s also the motif of sisterly rivalry and the comfort found in the household’s maid.

Speaking of rich imagery, in Bernarda Alba we have rumors of a woman riding naked in the olive grove. In Like Water for Chocolate, one of the sisters will ride off naked into the sunset with one of the revolutionaries. Both scenes represent liberation, both literal and symbolical. This is even more meaningful when we take into account that the story takes place in the early 1900s, during Mexican Revolution.

So what led to the Mexican Revolution and how does it tie to Like Water for Chocolate?

MEXICAN REVOLUTION (1910 – 1920)

Mexican Revolution is often referred to as the defining event of modern Mexican history. Simply put, Mexican Revolution is a series of armed conflicts that took place between 1910 and 1920. During this time, Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship was replaced by the revolutionary army.

However, what really happened was a complex political but also cultural process. Porfirio Díaz held power in Mexico for 7 long terms. His rule was justified by the economic prosperity although it mainly benefited the selected few and the foreign investors. This led to the dissatisfaction and crisis among the agrarian class.

Yet, the transition from Porfirio Díaz’s rule to the next stage was everything but smooth. The consequences of the Revolution can be seen to this day. In a way, it has shaped Mexican identity. Therefore, to understand the modern-day Mexico, we need to understand this crucial part of its history. So let’s start from the beginning.

THE SEEDS OF REVOLUTION

As you can assume, a dictatorship is upheld by ruling with an iron fist. So when a wealthy northern landowner Francisco Madero challenged Díaz in 1910, Díaz jailed him. He ended up releasing him and Madero called for revolution. Although this didn’t happen straight away, revolution was brewing all across Mexico.

Eventually, Díaz’s Federal Army couldn’t extinguish the widespread risings so he sought exile in Paris. Madero then took power but it was short-lived, no pun. His government was mostly fragile and he didn’t really plan to make big changes.

Simultaneously, the face of Mexican Revolution, the hero of peasants and indigenous people, Emiliano Zapata was rising. He demanded redistribution of land from rich landowners to the poor. However, this didn’t fit with Madero’s agenda, who was a rich landowner himself. In the end, he was assassinated in 1913 after one of his own, Victoriano Huerta, conspired against him. Thus more fight for power ensued and an even bloodier phase of Revolution began.

THE BLOODY FACE OF MEXICAN REVOLUTION

Much like his predecessor, Huerta’s rule didn’t last long. After suffering one defeat after another, the Federal Army was disbanded in 1914 and Huerta resigned.

Does that mean that the revolutionaries came to power and started making changes? Absolutely not. Instead, they divided into two factions and started fighting each other.

So who are these new factions and what do they stand for?

The Conventionists – led by Emiliano Zapata and Pancho Villa, required redistribution of land.

Constitutionalists – led by Venustiano Carranza and Álvaro Obregón, who mostly wanted they primacy of liberal reforms, with no real zeal for widespread changes in country’s social structure.

Therefore, the Mexican Revolution was really a civil war although there was some foreign intervention.

HOW THE UNITED STATES STARTED THE REVOLUTION

A significant event in Mexican Revolution was the bloody battle in April of 1915 in Celaya. Obregón’s forces defeated Villa so the Constitutionalist won the Revolution. Villa blamed Woodrow Wilson’s support of Carranza for losing against and thus began his vendetta against Americans in border regions.

Wilson then sent John J.Persting with a small force to pursue Villa and his bandits. This is partly the reason for the romanticized image of Pancho Villa that we have today. Even though his faction lost, they still fought valiantly against all odds.

WHAT DID THEY STAND FOR?

As the name indicates, the Constitutionalists brought the new Constitution in 1917. According to this Constitution, they were to:

- Confiscate land from wealthy landowners

- Guarantee workers’ rights

- Limit Roman Catholic Church’s rights

However, it also conferred dictatorial powers to the president so many of the revolutionary policies weren’t enacted upon until much later. The revolutionary army held office from 1920-1940 but it wasn’t until Lázaro Cárdenas came into power in 1936, that the changes started happening. He strengthened labour unions, nationalized Mexico’s oil industry and redistributed over 70,000 square miles of land.

And what happened with other relevant figures of Mexican Revolution? Zapata was assassinated in 1919 as well as Carranza in 1920, while Villa was murdered in 1923. Therefore, Mexican Revolution is a period known for violence and bloodshed on all levels.

As any complex political and social process, there was some genuine national interest. More than anything, though, it was about personal agendas and interests. And yet, it’s indisputable the legacy the Revolution has left to the modern Mexico. So let’s see what that is.

REVOLUTIONARY LEGACY

First and foremost, the Mexican Revolution ended Porfirio Díaz’s dictatorship. Furthermore, the Mexican Constitution doesn’t allow elected officials to run for a second term. It also stands for workers’ rights, it initiated many social and political reforms and it did reduce the power of the Catholic Church.

Revolution’s icons like Villa, Zapata, Carranza are still revered which is reflected through the national monuments and artistic depictions.

And most importantly, to this day, the PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional) or the Institutional Revolutionary Party has been almost undefeated.

We hope that you gained some insight into the Mexican Revolution and its significance for Mexico. Our learners always admit that understanding the cultural and historical background makes reading that much more engaging.

So how is the Revolution portrayed by Laura Esquivel and what influence it had on the story itself?

MEXICAN REVOLUTION IN LIKE WATER FOR CHOCOLATE

Firstly, there are two ways in which we can look at the topic of Mexican Revolution in the context of the novel.

One is factual, that is, Revolution as an actual event that is occurring at the same time as the story. We’re aware of what is happening on the national level, mostly through mentions in the passing. For instance, there’s awareness of bullets flying in the village and the fear of travel due to the Revolution raging across country.

Another one is symbolical, or the Revolution as a metaphor highlighting the theme of tradition vs. rebellion. Moreover, the Revolution happening in the background contributes to the feeling of restlessness so predominant in the story.

However, the Revolution in Like Water for Chocolate doesn’t always stay in the background. There are instances where the revolutionaries steer the plot and form part of the story.

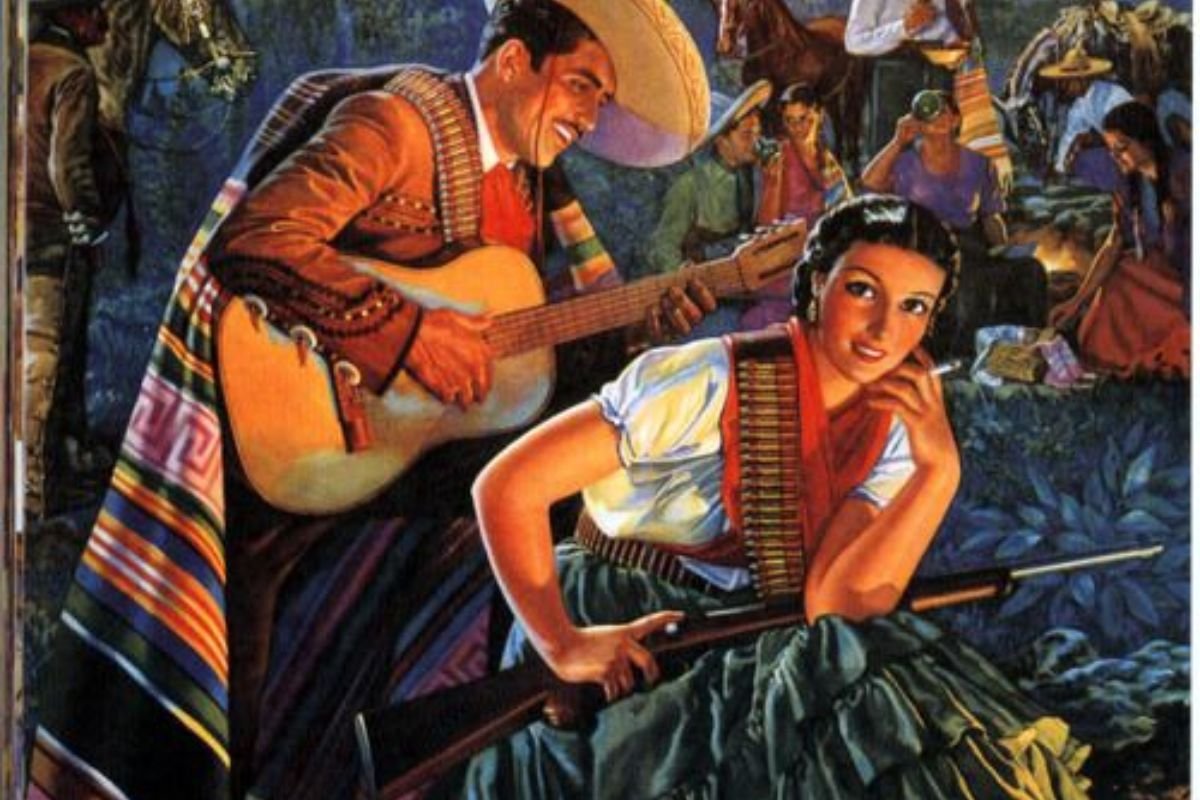

ROMANTIZATION OF THE REVOLUTION

We’ve already mentioned one such example, where the sister Gertrudis runs away with one of Villa’s men.

Overcome with desire, she can’t stop thinking about the man ‘smelling of sweat and mud, of dawns that brought uncertainty and danger, smelling of life and death.’

Gertrudis runs out naked and is picked up by the soldier she dreamt about.

‘Without slowing his gallop, so as not to waste a moment, he leaned over, put his arm around her waist, and lifted her onto the horse in front of him, face to face, and carried her away.’

We could argue that this is the romanticized image of the Revolution, with the rebelled party riding off into the sunset, liberated.

Gertrudis will reappear towards the end of the story as the general in the revolutionary army. Although she’s not the only sister who’s rebelled, hers is the most extreme and literal example precisely due to the connection to the revolutionaries.

TRADITION VS. REVOLUTION

There’s no doubt that tradition vs. revolution is the great theme of Like Water for Chocolate. On one hand, we can talk about revolution in terms of Tita discarding tradition imposed to her by her family. On the other, what happens when tradition clashes with the literal Revolution?

In the chapter five, we witness epic confrontation between the matriarch (tradition) and Villa’s men (Revolution). A revolutionary troop comes to the ranch demanding goods ‘to volunteer to help the cause.’

Mother Elena, who heard of the troop coming, hid everything valuable inside the house, including her daughters.

‘No one had ever had anything good to say about these revolutionaries. […] They had told her how the rebels entered houses, destroyed everything, and raped all the women in their path.’

It’s worth mentioning that she was told this by Father Ignacio. Given what we’ve learned about the conflict between the revolutionaries and the Catholic Church, this makes perfect sense.

However, in the end she admits that the way they came and left didn’t fit the picture of the heartless ruffians she’d been expecting. From that day on she would not express any opinion about the revolutionaries. As for the revolutionaries, they jokingly called her ‘general’ and voiced their admiration for such a brave and unyielding woman.

So there we have it, the face of tradition meets the face of Revolution – literally. Even such an impervious woman as Mother Elena admits to herself that the revolutionaries are not all that bad. This imposes an inevitable question: is all tradition bad?

THE IMPORTANCE OF TRADITIONAL FOOD

We see that Tita discards the tradition which makes no sense to her. If she looks after her mother and she never marries and has no children of her own, then who will look after her? Therefore, she comes to the conclusion that the system is faulty so she doesn’t want to abide by it.

Meanwhile, Tita’s life in the kitchen is everything but miserable even though that’s a very traditional role for a woman. What is more, she loves to cook. It’s how she expresses her love and remembers her life, through the smell and aroma of dishes. Without it, she feels lost.

As the very title of the book suggests, food has a central role. Even the story of Gertrudis’ runaway, among many others, was conditioned by food.

So let’s take a closer look at it.

FOOD AS CATALYST

When we say that many events were brought on by food, we mean that literally from the very start. Tita came into this world early because she was so sensitive to onion, she would cry relentlessly each time her mother was cutting it. This caused premature labor and so Tita was born in the kitchen, where she’d spend most of her life.

The novel itself is divided into 12 chapters and at the beginning of each we have a new recipe. In any other book, so much information about preparing food might result cumbersome to the reader. In Like Water for Chocolate, however, where so much revolves around food, it really adds to the warm, mouth-watering feel of the book.

Let’s see some famous scenes where food was the main protagonist:

Wedding cake

As punishment for protesting, Tita has to make the wedding cake for her sister Rosaura and Pedro. Overcome with sadness, she cries into the cake batter. This caused everyone who tried it to vomit and cry after their greatest love. It was a vomiting mayhem that ruined the wedding. Naturally, Mama Elena thought Tita poisoned the cake. Tita didn’t have her nanny Nacha to defend her because she was found dead in her bed, holding a picture of her lost love on her chest.

Quail in rose petal sauce

The secret ingredient to this family meal? Tita’s erotic thoughts of Pedro. This made her sister Gertrudis sweat pink, rose-scented sweat. When she tried to take a shower in the garden, her body was giving off so much heat, the shower itself caught fire. And that’s how Gertrudis ran out of the burning shower naked – straight into the arms of a revolutionary captain.

Three Kings’ Bread

The tradition revolving around Rosca de Reyes prompted Gertrudis to return to the ranch. She then purposefully revealed Tita’s suspected pregnancy to Pedro, which lead, as you can figure, to a whole new series of events.

FOOD AN FAMILY

As you can see just from these three examples, food is strongly associated with emotions and actions. The feelings that Tita puts into the food she makes affects those around her. But more than that, food is what brings the family together, despite their differences. It’s the tradition that brings the sense of community.

At one point, her sisters feel mournful at the thought of Tita dying because the whole culinary tradition would die with her, too.

It’s only appropriate that the novel ends the same way it started – with food.

‘I don’t know why mine (Christmas rolls) never turn out like hers, or why my tears flow so freely when I prepare them – perhaps I am as sensitive to onions as Tita, my great aunt, who will go on living as long as there is someone who cooks her recipes.’

Maybe you’ve even said this yourself – no one can cook that one dish like your mother/grandmother, etc. So maybe there is something to be said about the connection between emotions and preparation of food.

What most certainly doesn’t happen, however, are these seemingly impossible and ludicrous outcomes that we described. So why are they perceived as normal as cutting an onion? We’ve come to the recognizably Latin American genre called magical realism.

REALISMO MÁGICO

Magic realism, as we know it today, is a literary movement that officially started in the second half of the 20th century. Although its roots can be found elsewhere, we predominantly associate it with Latin America. This is mostly due to the publishing phenomenon called Latin American boom that really drew global attention to the Latin American authors. Classics like One Hundred Years of Solitude solidified and set up the stage for later, post-boom writers, including Laura Esquivel.

That being said, what is magical realism? And how do we classify a story as magic realism? In it, we’ll usually find:

REALISTIC SETTING

Unlike fantasy novels which are usually set up in a fantasy world, magical realism stories take place in the real world. In this case, Mexico during Revolution. Other genres like horror don’t fit the mold of magical realism because the otherworldly elements like ghosts are regarded as something extraordinary. Which brings us to the next point.

PERCEPTION OF MAGIC

Characters in magical realism stories don’t question magical elements in any way. Instead, they’re accepted as completely normal. No one wonders about the impossibility of the shower cabin combusting due to erotic thoughts. The events are simply narrated and described as it was any other everyday occurrence.

CRITIQUE

Even though there’s implied irony and humor in magical realism, it often serves to underlie an existing issue. As we’ve learned through Tita’s example, Like Water for Chocolate questions futile and backward traditions.

EXTENDED METAPHORE

Magical realism serves as a metaphor for the internal processes of characters. In that regard, Like Water for Chocolate might be one of the best examples for this due to the connection between food and emotions. For instance, the wedding cake soaked in Tita’s tears made everyone cry after their greatest love, emphasizing Tita’s suffering.

If you’d like to learn more about the movement itself, the boom phenomenon as well as other examples of magical realism, we’d like to direct you to our post on One Hundred Years of Solitude.

And now, let’s see what devices Laura Esquivel used to achieve the effect of magical realism.

RICH IN LITERARY DEVICES

We’ve already seen some pretty interesting and downright iconic scenes from Like Water for Chocolate. But how are they accomplished? Let’s take a look at the most frequently used literary devices. First and foremost, we’ll explain what those devices actually are.

HYPERBOLE

Hyperbole is a way of speaking or writing that makes something sound better, more exciting, dangerous, etc. than it really is.

We could argue that this is the magical realism literary device par excellance, as magical realism is an exaggeration in itself. Indeed, there are plenty of example of exaggeration in the novel.

For example, the way Gertrudis’ passion is described.

‘Her body was giving off so much heat that the wooden walls began to split and burst into flame.’

Obviously, this couldn’t happen, but the purpose of the hyperbole here was to highlight the intensity of Gertrudis’ feelings.

SYMBOLISM

A symbol is a person, an object, an event, etc. that represents a more general quality or concept.

In Like Water for Chocolate, there’s plenty of imagery, mostly associated with food/feelings.

Rose

Red roses are universal symbol for passion and romantic love. Let’s just remember how Tita prepared those quails with rose petals and the effect that had.

Tita’s bedspread

One of the most pictoric symbols is definitely the bedspread Tita began making for her wedding with Pedro. It’s made of all sorts of colors and fabrics. This makes sense when we think of it as representation of Tita’s innermost feelings. She comes back to it whenever she’s distraught and needs something to occupy her mind. By the end, the bedspread is large enough to cover the entire ranch.

Fire

Fire and heat might be the most frequently used symbols in Like Water for Chocolate. Just like roses, fire is a universal symbol for passion. It’s not for nothing that we say fiery passion. Moreover, it’s needed for cooking so the symbolism of fire comes as no surprise in the context of the novel. However, it can also represent anger. When Tita hears that Rosaura wants to continue the family tradition through her only daughter, Tita begins boiling ‘like water for chocolate.’

Cold

Throughout the story, Tita experiences bouts of cold that have nothing to do with weather. The first time this happens is when she finds out Pedro is to marry her sister. Other times, she was overcome with cold when Pedro was forbidden from complimenting her food and when her nephew dies. In the end, she becomes so desperate to rekindle her inner fire, she eats matches. Thus, cold represents isolation and unhappiness.

CONTINUATION OF TITA’S STORY

Even though Like Water for Chocolate can stand on its own, did you know it’s actually part of a trilogy?

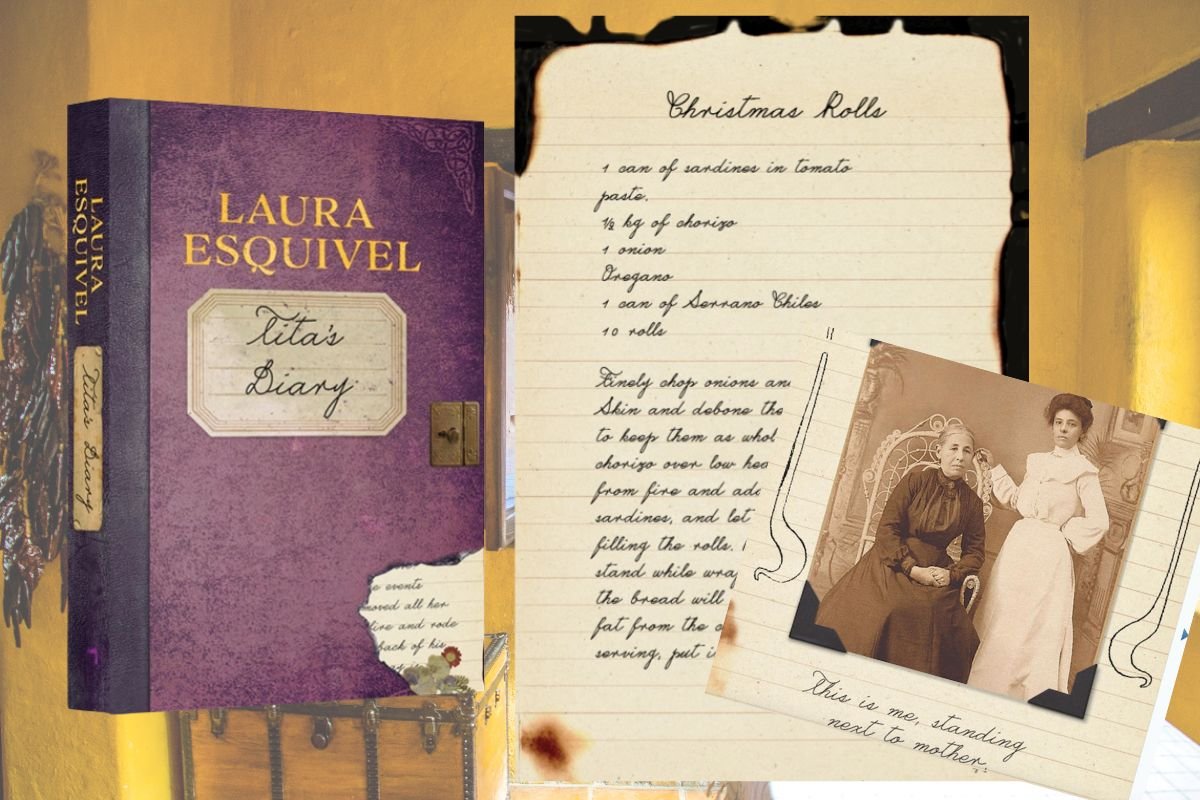

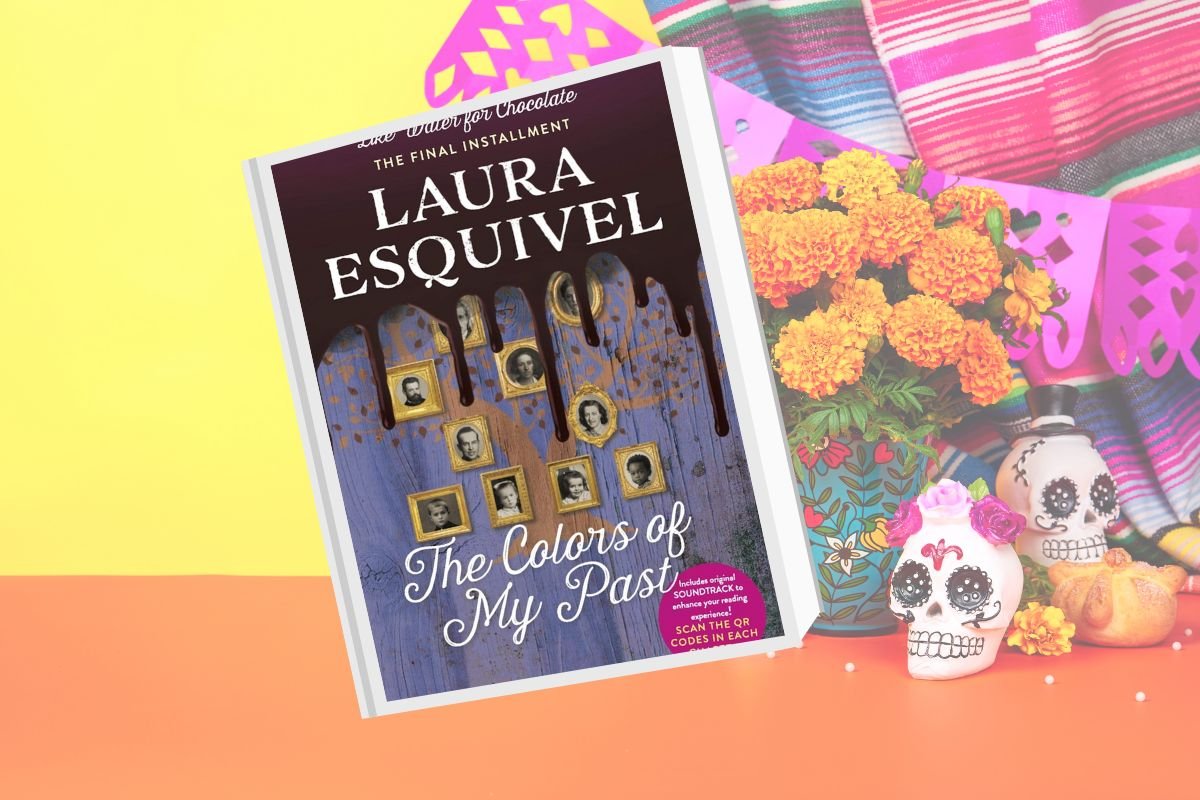

Laura Esquivel also published Tita’s Diary and another sequel, The Colors of my Past. So what can you expect from it?

The Colors of my Past follows María, a descendant of Tita. The first and most important thing they have in common: love for food. After being abandoned by her husband, María is saved by her grandmother Lucía, who leads her to discover Tita’s diary. This, in turn, makes her connect to her roots and discover family secrets. Just like Tita’s Diary, it comes with some interesting extras. The original soundtrack is there to enhance your reading experience by scanning the QR code in each chapter.

All in all – a good way to stay a bit longer in the world Laura Esquivel has created.

Like Water for Chocolate is an indisputable classic of not just Mexican, but world literature.

We’ve closely examined some of the key ingredients that made it so successful. The story of Tita is set in the backdrop of Mexican Revolution, an interesting and influential period in Mexico’s history. The theme of Revolution is both literal and metaphorical, as Tita herself will rebel against her authoritarian mother.

Another factor that makes Like Water for Chocolate such a compelling story is the genre it belongs to. We’ve pointed out some of the most iconic magical realism moments, like the shower cabin catching fire due to Gertrudis’ passion.

We’ve also explained and gave examples for some of the most frequently used literary devices. This includes hyperbole, a myriad of symbols like roses, fire, Tita’s bedspread, etc. We’ve come to the conclusion that the entire story can be interpreted as an allegory, a representation of Mexican Revolution.

And if you’d like to stay in the story a bit longer, we recommend that you read the sequels. Tita’s Diary and The Colors of my Past will bring you even more family secrets, music and, of course – food.

LEARN SPANISH THROUGH MOVIES WITH ROMANCE

We hope you liked the review of Like Water for Chocolate. If you’d like to give us your own opinion on it, we invite you to join out newly opened Book Club!

We meet every month to discuss a popular book of choice. You can read the book in any language you like, but the discussion will always be in Spanish, which makes this for a great practice if your speaking skills are rusty or in need of developing.

Our professional tutor will have materials ready for each class to make this an engaging and valuable experience. You will not only be reading for the sake of a good story, but you will also be learning about culture and history of Latin America and Spain through literature.

The next book on our TBR list is The Time in Between by María Dueñas. For all updates and future announcement, you can follow us either on our website or our Instagram page.

We’ll be publishing the flashcards on our Instagram page so feel free to follow us for more. If you want to learn Spanish with us, come and meet us, we would love to answer all your questions!